“If you always do what you’ve always done, you’ll always get what you’ve always got.”

– Henry Ford (supposedly)

Manufacturing excellence is a broad term. For some manufacturers it represents simply a production benchmark, a set of “world-class” manufacturing standards to model themselves on to achieve higher profitability; while for others, it’s a part of an overall commitment to meet and exceed internal goals that encompass safety, machine performance and plant capacity, employee training and satisfaction, customer service and deep organizational change, just a part of an overall program for operational excellence.

We see analytics and machine monitoring as just one of the must-dos needed in order to achieve your manufacturing excellence goals, and in a series of blogs on the subject, we’ll aim to provide some practical guidelines to help manufacturers do what they do already, just with better results.

We aren’t Lean manufacturing specialists or Black Belts, but we are well-versed in what makes great manufacturing companies even better. In part, because we work with discerning customers, who value Mingo data precisely because they are committed to manufacturing excellence and want to measure the impact of their initiatives. When possible, we’ve reached out to our colleagues and customers to see how they do things, and we’re putting a lot of time into researching what great companies are doing, all so we can understand better how manufacturing analytics can play a critical role in helping them succeed.

Defining Manufacturing Excellence

We’ve cobbled together a definition borrowed from the best documented Lean methodologies, and define it as:

The sustainable, continuous improvement of operations to gain a competitive advantage, lower costs, and increase profit.

In other words, doing more of what you do, more efficiently and with a higher level of quality, so you can sell more of it.

That means measuring some key KPIs on performance. (Here’s a few we recommend.) But there’s more to manufacturing excellence than just raising OEE or lowering the number of rejected parts produced. It’s all about having a great manufacturing culture.

Most programmatic approaches to achieving manufacturing excellence are founded on some or all of the Lean manufacturing principles, but it’s nice when someone can sum up these complex systems in a broad way, succinctly:

“Operational excellence is when each employee can see the flow of value to the customer—and fix that flow when it breaks down. It’s that simple.”

– Kevin Duggan, faculty member, Lean Enterprise Institute

Lean Manufacturing

Rather than go too deeply into what these methodologies are and how they work, we’re better off highlighting some of their core principles.

In their simplest forms, these methodologies of manufacturing excellence are all about eliminating waste (lean) and reducing variation in the production process (reliability).

Any approach to manufacturing excellence owes a huge debt to Dr. Shigeo Shingo. The idea of continuous change is a key concept embodied in Kaizen, or “change for better”. Always meant to be a continuous effort, Kaizen is a holistic philosophy of manufacturing, though more modern applications focus on using the tools instead of on “Kaizen events”– high energy, short-duration sprints to fix prioritized issues in production.

Better aligned with Shingo’s more holistic and continuous system is the concept of the Five S’s, a set of priorities meant to encourage employees to engage in focused improvement every day. These are translated into English as Sort, Set In order, Shine, Standardize and Sustain.

When employees take ownership of their machines and their workplace, and it’s obvious they are implementing the Five S’s, they are engaged and involved. To Shingo, these are the visible aspects of the Lean manufacturing approach and the necessary conditions for creating sustained improvement.

Shingo was also a huge proponent of visual systems of control and improvement. He advocated strongly for Kanban visual management tools and other scoreboards, making the invisible, visible at all levels of the manufacturing process. He also pioneered data gathering and manufacturing KPIs with OEE, a way of averaging a plant or machine’s efficiency.

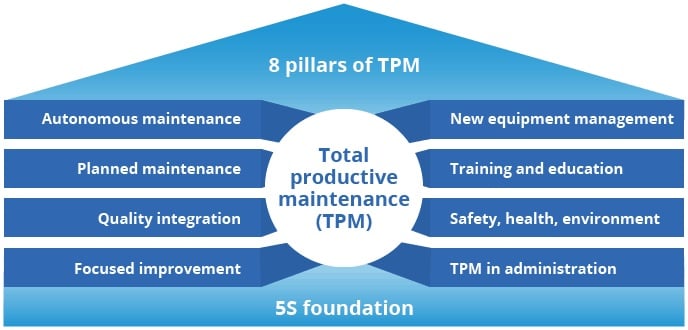

Total Productive Maintenance (TPM)

Total Productive Maintenance (TPM) was first introduced in Japan by Seiichi Nakajima and borrowed heavily on Lean principles. If the focus of Lean was primarily the reduction of waste in all of its forms, TPM aimed for performance and reliability, with a stated goal of 0% equipment failure.

To implement TPM, manufacturers need to focus on at least 8 pillars:

- Autonomous Maintenance

- Focused Improvement

- Planned Maintenance

- Quality management

- Early/equipment management

- Education and Training

- Administrative & office TPM

- Safety Health Environment

To operate competitively in an automated world and pursue “world-class” manufacturing excellence, more and more manufacturers will adopt formal programs like Lean and TPM or Six Sigma, but most likely will end up borrowing freely from all of them, using what makes sense for them.

Fostering Ownership

Kevin Duggan suggests that implementing Lean methodologies isn’t enough. He describes common mistakes organizations make when managers use Lean as a one-off tool to solve one-off problems but it is not embraced as part of an overall mindset and cultural prerogative.

“One of the biggest mistakes I see is when management and leadership try to drive operational excellence,” Duggan says, “Issues arise when management teams see the metrics and then control the initiatives. They say to employees ‘Go fix this area’ and throw resources, time and money at an issue. That philosophy is wrong.”

His big push is for ownership of continuous improvement and Lean processes, from the operators on the plant floor to the c-suite executives, back-office to the sales and marketing staff.

The theory is sound. If operators have ownership of their equipment, meaning they have a stake in maintaining and optimizing their performance, then a lot of big issues can be avoided and a lot of little problems get solved.

By measuring machine and cell performance then, performance numbers like optimized cycle time, a high first-pass yield, and increased throughput can attest to their hard work and discipline. These numbers are just as visible and obvious as a well-maintained machine and a clean work environment. The proof is in the data.

The idea around plant-floor visibility is that data is available to everyone, to the operators, the managers, and the executives. Give your employees a measurement of their improved performance (or an indication that there’s an issue they can address), and they’ll own those numbers too. It’s all about making continuous improvement part of a daily workflow.

Total Productive Maintenance – Is it Strictly Necessary?

“The fact is machines do virtually 100 percent of the product manufacturing work. The only thing people do, whether we’re operators, technicians, engineers, or managers, is tend to the needs of the machines one way or another. The better our machines run, the more productive our shop floor, and the more successful our business.”

James Leflar, Practical TPM, 2001

In James Leflar’s case that was especially true. As an engineer on Agilent’s semiconductor team, he launched the pilot for the Total Productive Maintenance (TPM) program in the early 2000s. The program was designed to reduce breakdowns and increase quality.

For Agilent, then a newborn spinoff of Hewlett-Packard making semiconductor wafers, minimizing equipment failure, and optimizing performance were critical to its success. Computer chips and circuit boards require precision manufacturing, sometimes with machines operating within a vacuum environment completely out of view from the operators.

Here’s Leflar again describing the importance of TPM to the company:

“In many factories, such as automobile assembly plants, there is a strong interaction among operators, their machines and the manufactured product. In these situations, the condition of the machines and the quality of the products are usually apparent to the machine operators.This is not true of IC (Integrated Circuit) Fab,” Leflar says. “Because of this distant relationship between operators, their equipment and the manufactured product, maintaining optimal machine conditions is extremely critical in the IC industry.”

In Agilent’s case, with a noticeable lack of first-hand visibility, monitoring equipment through remote sensor technologies and adopting a TPM program was Agilent’s best defense against asset failure and quality issues. It was a program borne out of necessity.

With ever-increasing automation and robot-assisted manufacturing techniques, more and more manufacturers will task their operators with maintaining highly complex machines in a highly automated production environment, perhaps even operating machines remotely. They too may find that TPM offers a strong value proposition by increasing reliability and performance.

For others, the excess costs associated with implementing Total Productive Maintenance are simply too great to justify. According to the Marshall Institute, an asset management consulting and training company, companies can expect an increase in training costs of 10 or even 20%, plus another 15% for additional maintenance costs.

The stark alternative to TPM, i.e. running their equipment to failure, isn’t a sign they don’t care. For some, it’s a conscious decision based on perceived ROI, especially when the additional costs for TPM are known to be substantial but the savings are hard to quantify.

In a follow-up with Leflar, he understands that not every company can or should implement TPM, “Implementing TPM in its totality is rarely achieved in American companies…However, the TPM activities that are traditionally carried out within the maintenance department, could shift to operators, which I believe would benefit any manufacturing operation.”

If a manufacturer is on the fence about it, there’s no reason why they can’t pilot a program on a part of the line that seems most prone to breakdowns, implementing TPM and then measuring to see if the effort makes a dent in downtime or increased capacity and making sure any gains are sustained.

Regardless of how they approach a productive maintenance program, in order to see success and determine whether they are indeed improving on productivity, they will need to start tracking KPIs and measuring machine performance.

With Visibility, Comes Clarity

We feel pretty strongly that adopting any methodology that embraces continuous improvement is worthwhile, but that the keys to improvement aren’t having an army of Black Belts on your staff, but empowering your existing staff with better data, visibility into the production process and what’s working or not and encouraging them to always make evidence-based decisions on everything from preventative maintenance to root cause analysis.